Knee replacement

Definition

Knee replacement is a procedure in which the surgeon removes damaged or diseased parts of the patient's knee joint and replaces them with new artificial parts. The operation itself is called knee arthroplasty . Arthroplasty comes from two Greek words, arthros or joint and plassein , "to form or shape." The artificial joint itself is called a prosthesis. Most knee prostheses have four components or parts, and are made of a combination of metal and plastic, or metal and ceramic in some newer models.

Purpose

Knee arthroplasty has two primary purposes: pain relief and improved functioning of the knee joint. Because of the importance of the knee to a person's ability to stand upright, improved joint functioning includes greater stability in the knee.

Pain relief

Total knee replacement, or TKR, is considered major surgery. Therefore, it is usually not considered a treatment option until the patient's pain cannot be managed any longer by more conservative treatment. Alternatives to surgery are described below.

Pain in the knee may be either a sudden or gradual development, depending on the cause of the pain. Knee pain resulting from osteoarthritis and other degenerative disorders may develop gradually over a period of years. On the other hand, pain resulting from an athletic injury or other traumatic damage to the knee, or from such conditions as infectious arthritis or gout, may come on suddenly. Because the structure of the knee is complex and many different disorders or conditions can cause knee pain, the cause of the pain must be diagnosed before joint replacement surgery can be discussed as an option.

Joint function

Restoration of joint function and stability is the other major purpose of knee replacement surgery. It is helpful to have a brief outline of the major structures in the knee joint in order to understand the types of disorders and injuries that can make joint replacement necessary as well as to understand the operation itself.

The knee is the largest joint in the human body, as well as one of the most vulnerable. Unlike the hip joint, which is partly protected by the bony structures of the pelvis, the knee joint is not shielded by any other parts of the skeleton. In addition, the knee joint must bear the weight of the upper body as well as the stresses and shocks carried upward through the feet when a person walks or runs. Moreover, the knee is essentially a hinge joint, designed to move primarily backwards and forwards; it is not a ball-and-socket joint like the hip, which can swivel and rotate in a variety of directions. Many knee injuries result from stresses caused by twisting or turning movements, particularly when the foot remains in one position while the upper body changes direction rapidly, as in basketball, tennis, or skiing.

The normal knee joint consists of a bone, the patella or kneecap, and a set of tendons, ligaments, and cartilage disks that connect the femur, or thighbone, to the lower leg. There are two bones in the lower leg, the tibia, which is sometimes called the shinbone; and the fibula, a smaller bone on the outside of the lower leg. There are two collateral ligaments on the outside of the knee joint that connect the femur to the tibia and fibula respectively. These ligaments help to control the stresses of side-to-side movements on the knee. The patella—a triangular bone at the front of the knee—is attached by tendons to the quadriceps muscles of the thigh. This tendon allows a person to straighten the knee. Two additional tendons inside the knee stretch between the femur and the tibia to prevent the tibia from moving out of alignment with the femur. Cartilage, which is a whitish elastic tissue that allows bones to glide smoothly against each other, covers the ends of the femur, tibia, and fibula as well as the surfaces of the patella. In addition to the cartilage that covers the bones, the knee joint also contains two crescent-shaped disks of cartilage known as menisci (singular, meniscus), which lie between the lower end of the femur and the upper end of the tibia and act as shock absorbers or cushions. The entire joint is surrounded by a thick layer of protective tissue known as the joint capsule.

Disorders and conditions that may lead to knee replacement surgery include:

- Osteoarthritis (OA). Osteoarthritis is a disorder in which the cartilage in the knee joint gradually breaks down, allowing the surfaces of the bones to rub directly against each other. The patient experiences swelling, pain, inflammation, and increasing loss of mobility. OA most often affects adults over age 45, and is thought to result from a combination of wear and tear on the joint, lifestyle, and genetic factors. As of 2003, OA is the most common cause of joint damage requiring knee replacement.

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Rheumatoid arthritis is a disease that begins earlier in life than OA and affects the whole body. Women are three times as likely as men to develop RA. Its symptoms are caused by the immune system's attacks on the body's own cells and tissues. Patients with RA often suffer intense pain even when they are not putting weight on the affected joints.

- Trauma. Damage to the knee from a fall, automobile accident, or workplace or athletic injury may trigger the process of cartilage breakdown inside the joint. Trauma is a common cause of damage to the knee joint. Some traumatic injuries are caused by repetitive motion or overuse of the knee joint; these types of injury include bursitis, or housemaid's knee, and so-called runner's knee. Other traumatic injuries are caused by sudden twisting of the knee, a direct blow to a bent knee, or being tackled from the side in football.

There are several factors that increase a person's risk of eventually requiring knee replacement surgery. While some of these factors cannot be avoided, others can be corrected through lifestyle changes:

- Genetic. Both OA and RA tend to run in families. One study done in France reported that the genetic factors affecting osteoarthritis in the knee can be traced back almost 8,000 years. Both OA and RA, however, are polygenic disorders, which means that more than one gene is involved in transmitting susceptibility to these forms of arthritis.

- Age. Knee cartilage becomes thinner and weaker with age, even in people who have no family history of arthritis.

- Sex. Women athletes have three times as many knee injuries as men. At present, orthopedic specialists are conducting studies to determine the cause(s) of this difference. Some doctors think it is related to the fact that most women have wider hips than most men, which results in a different pattern of stresses on the knee joint. Others think that the ligaments in women's knees tend to loosen more easily.

- Biomechanical. Biomechanics refers to the study of body structures in terms of the laws of mechanics, such as measuring the forces that affect the operation of a joint. Biomechanical studies have shown that people with certain types of leg or foot deformities, such as bowlegs or difference in leg length, are at increased risk of knee disorders because the stresses on the knee joint are not distributed normally.

- Gait-related factors. Gait refers to a person's pattern of motion when walking or running. Some people walk with their feet turned noticeably outward or inward; others tend to favor either the heel or the toe when they walk, which makes their gait irregular. Any of these factors can increase strain on the knee joint.

- Shoes. Poorly fitted or worn-out shoes contribute to knee strain by increasing the force transmitted upward to the knee when the foot strikes the sidewalk or other hard surface. They also introduce or increase irregularities in gait. Women's high-heeled shoes are particularly harmful to the knee joint because they do not cushion the foot; and they cause prolonged tightening and fatigue of the leg muscles.

- Work or other activities that involve jumping, jogging, or squatting. Jogging tends to loosen the ligaments that hold the parts of the knee joint in alignment, while jumping increases the shock on the knee joint and the risk of twisting or tearing the knee joint when the person lands. Squatting can increase the forces on the knee joint as much as eight times body weight.

Demographics

According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), there are about 270,000 knee replacement operations performed each year in the United States. Although about 70% of these operations are performed in people over the age of 65, a growing number of knee replacements are being done in younger patients. A Canadian survey released in January 2003 stated that the number of knee replacements performed in patients younger than 55 rose 90% between 1994 and 2001. Most surgeons expect to see the proportion of knee arthroplasties performed in younger patients continue to rise. One reason for this trend is improvements in surgical technique, as well as the design and construction of knee prostheses since the first knee replacement was performed in 1968. Although most knee prostheses are still cemented in place as of 2003, cementless prostheses were introduced in the 1980s. A second reason is people's changing attitudes toward aging and their expectations of an active life after retirement. Fewer are willing to endure years of discomfort or resign themselves to a restricted level of activity.

In terms of gender and racial differences, women are slightly more likely to seek knee replacement surgery than men, and Caucasians in the United States are more likely to have the operation than African Americans. Researchers have suggested that one reason for the racial difference is a difference in social networks. People in general are influenced in their health care decisions by the experiences and opinions of friends or family members, and Caucasians are more likely than African Americans to know someone who has had knee replacement surgery.

Description

The length and complexity of a total knee replacement operation depend in part on whether both knee joints are replaced during the operation or only one. Such disorders as osteoarthritis usually affect both knees, and some patients would rather not undergo surgery twice. Replacement of both knees is known as bilateral TKR, or bilateral knee arthroplasty. Bilateral knee replacement seems to work best for patients whose knees are equally weak or damaged. Otherwise most surgeons recommend operating on the more painful knee first so that the patient will have one strong leg to help him or her through the recovery period following surgery on the second knee. The disadvantages of bilateral knee replacement include a longer period of time under anesthesia; a longer hospital stay and recovery period at home; and a greater risk of severe blood loss and other complications during surgery.

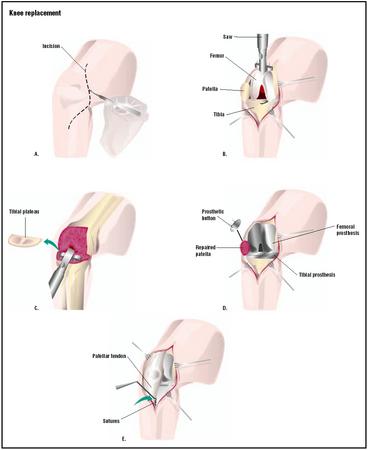

If the operation is on only one knee, it will take two to four hours. The patient may be given a choice of general, spinal, or epidural anesthesia. An epidural anesthetic, which is injected into the space around the spinal cord to block sensation in the lower body, causes less blood loss and also lowers the risk of blood clots or breathing problems after surgery. After the patient is anesthetized, the surgeon will make an incision in the skin over the knee and cut through the joint capsule. He or she must be careful in working around the tendons and ligaments inside the joint. Knee replacement is a more complicated operation than hip replacement because the hip joint does not depend as much on ligaments for stability. The next step is cutting away the damaged cartilage and bone at the ends of the femur and tibia. The surgeon reshapes the end of the femur to receive the femoral component, or shell, which is usually made of metal and attached with bone cement.

After the femoral part of the prosthesis has been attached, the surgeon inserts a metal component into the upper end of the tibia. This part is sometimes pressed rather than cemented in place. If it is a cementless prosthesis, the metal will be coated or textured so that new bone will grow around the prosthesis and hold it in place. A plastic plate called a spacer is then attached to the metal component in the tibia. The plastic allows the femur and tibia to move smoothly against each other.

Lastly, another plastic component is glued to the rear of the patella, or kneecap. This second piece of plastic prevents friction between the kneecap and the other parts of the prosthesis. After all the parts of the prosthesis have been implanted, the surgeon will check them for proper positioning, make certain that the tendons and ligaments have not been damaged, wash out the incision with sterile saline solution, and close the incision.

Diagnosis/Preparation

Patient history

The first part of a diagnostic interview for knee pain is the careful taking of the patient's history. The doctor will ask not only for a general medical history, but also about the patient's occupation, exercise habits, past injuries to the knee, and any gait-related problems. The doctor will also ask detailed questions about the patient's ability to move or flex the knee; whether specific movements or activities make the pain worse; whether the

Diagnostic tests

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF THE KNEE. Following the history, the doctor will examine the knee itself. The knee will be checked for swelling, reddening, bruises, breaks in the skin, lumps, or other unusual features while the patient is standing. The doctor will also make note of the patient's posture, including whether the patient is bowlegged or knock-kneed. The patient may be asked to walk back and forth so that the doctor can check for gait abnormalities.

In the second part of the physical examination , the patient lies on an examining table while the doctor palpates (feels) the structures of the knee and evaluates the strength or tightness of the tendons and ligaments. The patient may be asked to flex one knee and straighten the leg or turn the knee inward and outward so that the doctor can measure the range of motion in the joint. The doctor will also ask the patient to lie still while he or she moves the knee in different directions.

IMAGING STUDIES. The doctor will order one or more imaging studies in order to narrow the diagnosis. A radiograph or x ray is the most common, but is chiefly useful in showing fractures or other damage to bony structures. X-ray studies are usually supplemented by other imaging techniques in diagnosing knee disorders. A computed tomography, or CAT scan, which is a specialized type of x ray that uses computers to generate three-dimensional images of the knee joint, is often helpful in evaluating malformations of the joint. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses a large magnet, radio waves, and a computer to generate images of the knee joint. The advantage of an MRI is that it reveals injuries to ligaments, tendons, and menisci as well as damage to bony structures.

ASPIRATION. Aspiration is a procedure in which fluid is withdrawn from the knee joint by a needle and sent to a laboratory for analysis. It is done to check for infection in the joint and to draw off fluid that is causing pain. Aspiration is most commonly done when the knee has swelled up suddenly, but may be performed at any time. Blood in the fluid usually indicates a fracture or torn ligament; the presence of bacteria indicates infection; the presence of uric acid crystals indicates gout. Clear, straw-colored fluid suggests osteoarthritis.

ARTHROSCOPY. Arthroscopy can be used to treat knee problems as well as diagnose them. An arthroscope consists of a miniature camera and light source mounted on a flexible fiberoptic tube. It allows the surgeon to look into the knee joint. To perform an arthroscopy, the surgeon will make two to four small incisions known as ports. One port is used to insert the arthroscope; the second port allows insertion of miniaturized surgical instruments ; the other ports drain fluid from the knee. Sterile saline fluid is pumped into the knee to enlarge the joint space and make it easier for the surgeon to view the knee structures and to cut, smooth, or repair damaged tissue.

Preoperative preparation

Knee replacement surgery requires extensive and detailed preparation on the patient's part because it affects so many aspects of life.

LEGAL AND FINANCIAL CONSIDERATIONS. In the United States, physicians and hospitals are required to verify the patient's insurance benefits before surgery and to obtain precertification from the patient's insurer or from Medicare . Without health insurance, the total cost of a knee replacement as of early 2003 can run as high as $38,000. In addition to insurance documentation, patients are legally required to sign an informed consent form prior to surgery. Informed consent signifies that the patient is a knowledgeable participant in making health-care decisions. The doctor will discuss all of the following with the patient before he or she signs the form: the nature of the surgery; reasonable alternatives to the surgery; and the risks, benefits, and uncertainties of each option. Informed consent also requires the doctor to make sure that the patient understands the information that has been given.

MEDICAL CONSIDERATIONS. Patients are asked to do the following in preparation for knee replacement surgery:

- Get in shape physically by doing exercises to strengthen or increase flexibility in the knee joint. Specific exercises are described in the books listed below. Many clinics and hospitals also distribute illustrated pamphlets of preoperation exercises.

- Lose weight if the surgeon recommends it.

- Quit smoking. Smoking weakens the cardiovascular system and increases the risks that the patient will have breathing difficulties under anesthesia.

- Make donations of one's own blood for storage in case a transfusion is necessary during surgery. This procedure is known as autologous blood donation ; it has the advantage of avoiding the risk of transfusion reactions or transmission of diseases from infected blood donors.

- Check the skin of the knee and lower leg for external infection or irritation, and check the lower leg for signs of swelling. If either is noted, the surgeon should be contacted for instructions about preparing the skin for the operation.

- Have necessary dental work completed before the operation. This precaution is necessary because small numbers of bacteria enter the bloodstream whenever a dentist performs any procedure that causes the gums to bleed. Bacteria from the mouth can be carried to the knee area and cause an infection.

- Discontinue taking birth control pills and any anti-inflammatory medications ( aspirin or NSAIDs) two weeks before surgery. Most doctors also recommend discontinuing any alternative herbal preparations at this time, as some of them interact with anesthetics and pain medications.

LIFESTYLE CHANGES. Knee replacement surgery requires a long period of recovery at home after leaving the hospital. Since the patient's physical mobility will be limited, he or she should do the following before the operation:

- Arrange for leave from work, help at home, help with driving, and similar tasks and commitments.

- Obtain a handicapped parking permit.

- Check the house or apartment thoroughly for needed adjustments to furniture, appliances, lighting, and personal conveniences. People recovering from knee replacement surgery must avoid kneeling, and minimize bending, squatting, and any risk of falling. There are several good guides available that describe household safety and comfort considerations in detail.

- Stock up on nonperishable groceries, cleaning supplies, and similar items in order to minimize shopping.

- Have a supply of easy-care clothing with elastic waistbands and simple fasteners in front rather than complicated ties or buttons in the back. Women may find knit dresses that pull on over the head or wraparound skirts easier to put on than slacks or skirts that must be pulled up over the knees. Shoes should be slip-ons or fastened with Velcro.

Many hospitals and clinics now have "preop" classes for patients scheduled for knee replacement surgery. These classes answer questions about the operation and what to expect during recovery, but in addition they provide an opportunity for patients to share concerns and experiences. Studies indicate that patients who have attended preop classes are less anxious before surgery and generally recover more rapidly.

Aftercare

Aftercare following knee replacement surgery begins while the patient is still in the hospital. Most patients will remain there for five to 10 days after the operation. During this period the patient will be given fluids and antibiotic medications intravenously to prevent infection. Medications for pain will be given every three to four hours, or through a device known as a PCA (patient-controlled anesthesia). The PCA is a small pump that delivers a dose of medication into the IV when the patient pushes a button. To get the lungs back to normal functioning, a respiratory therapist will ask the patient to cough several times a day or breathe into blow bottles.

Aftercare during the hospital stay is also intended to lower the risk of a venous thromboembolism (VTE), or blood clot in the deep veins of the leg. Prevention of VTE involves medications to thin the blood; exercises for the feet and ankles while lying in bed; and wearing thromboembolic deterrent (TED) or deep vein thrombosis (DVT) stockings. TED stockings are made of nylon (usually white) and may be knee-length or thigh-length; they help to reduce the risk of a blood clot forming in the leg vein by putting mild pressure on the veins.

Physical therapy is also begun during the patient's hospital stay, often on the second day after the operation. The physical therapist will introduce the patient to using a cane or crutches and explain how to manage such activities as getting out of bed or showering without dislocating the new prosthesis. In most cases the patient will spend some time each day on a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine, which is a device that repeatedly bends and straightens the leg while the patient is lying in bed. In addition to increasing the patient's level of physical activity each day, the physical therapist will help the patient select special equipment for recovery at home. Commonly recommended devices include tongs or reachers for picking up objects without bending too far; a sock cone and special shoehorn; and bathing equipment.

Following discharge from the hospital , the patient may go to a skilled nursing facility, rehabilitation center, or home. Patients who have had bilateral knee replacement are unlikely to be sent directly home. Ongoing physical therapy is the most important part of recovery for the first four to five months following surgery. Most HMOs in the United States allow home visits by a home health aide, visiting nurse, and physical therapist for three to four weeks after surgery. Some hospitals allow patients to borrow a CPM machine for use at home for a few weeks. The physical therapist will monitor the patient's progress as well as suggest specific exercises to improve strength and range of motion. After the home visits, the patient is encouraged to take up other forms of low-impact physical activity in addition to the exercises; swimming, walking, and pedaling a stationary bicycle are all good ways to speed recovery. The patient may take a mild medication for pain (usually aspirin or ibuprofen) 30–45 minutes before an exercise session if needed.

The patient will be instructed to notify his or her dentist about the knee replacement so that extra precautions can be taken against infection resulting from bacteria getting into the bloodstream during dental work. Some surgeons ask patients to notify them whenever the dentist schedules a tooth extraction , root canal, or periodontal work.

Risks

Serious risks associated with TKR include the following:

- Loosening or dislocation of the prosthesis. The risk of dislocation varies, depending on the type of prosthesis used, the patient's level of activity, and the previous condition of the knee joint.

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT). There is some risk (about 1.5% in the United States) of a clot developing in the deep vein of the leg after knee replacement surgery because the blood supply to the leg is cut off by a tourniquet during the operation. The blood-thinning medications and TED stockings used after surgery are intended to minimize the risk of DVT.

- Infection. The risk of infection is minimized by storing autologous blood for transfusion and administering intravenous antibiotics after surgery. The rate of infection following knee replacement is about 1.89%. Factors that increase the risk of infection after TKR include poor nutritional status, diabetes, obesity, a weakened immune system, and a history of smoking.

- Heterotopic bone. Heterotopic bone is bone that develops at the lower end of the femur after knee replacement surgery. It is most likely to develop in patients whose knee joints developed an infection. Heterotopic bone can cause stiffness and pain, and usually requires revision surgery.

Normal results

Normal results include relief of chronic pain in the knee and greater range of motion in the knee joint. Realistically, however, the patient should not expect complete restoration of function in the knee, and will usually be advised to avoid contact sports, skiing, jogging, or other athletic activities that strain the knee joint.

Mild swelling of the leg may occur for as long as three to six months after surgery. It can be treated by elevating the leg, applying an ice pack, and wearing compression stockings.

One commonplace side effect of TKR is that knee prostheses sometimes set off metal detectors in airports and high-security buildings because of their large metal content. Patients who fly frequently or whose occupations require security clearance should ask their doctor for a wallet card certifying that they have a knee prosthesis.

The patient can expect a cemented knee prosthesis to last about 10–15 years, although many still function well as long as 20 years later. Cementless prostheses have not been in use long enough for reliable evaluations of their long-term durability. When the prosthesis wears out or becomes loose, it is replaced in a procedure known as knee revision surgery .

Morbidity and mortality rates

A study published in 2002 reported that the 30-day mortality rate following total knee arthroplasty was 0.5%. The overall frequency of serious complications in this time period was 2.2%. This figure included 0.4% heart attack; 0.7% pulmonary embolism; and 1.5% deep venous thrombosis. The rate of complications was highest in patients over 70, and male patients were more likely to have heart attacks than women.

A 2001 study published by the Mayo Clinic reviewed the records of 22,540 patients who had had knee replacements between 1969 and 1997. The mortality rate within 30 days of surgery was 0.21%, or 47 patients. Forty-three of the 47 patients had had preexisting cardiovascular or lung disease. Patients who had had bilateral knee operations had a higher mortality rate than those who had not.

Alternatives

Nonsurgical alternatives

MEDICATION. The most common conservative alternatives to knee replacement surgery are analgesics , or painkilling medications. Most patients who try medication for knee pain begin with an over-the-counter NSAID such as ibuprofen (Advil). If the pain cannot be controlled by nonprescription analgesics, the doctor may give the patient cortisone injections, which relieve the pain of arthritis by reducing inflammation. Unfortunately, the relief provided by cortisone tends to diminish with each injection; moreover, the drug can produce serious side effects.

If the knee pain is caused by rheumatoid arthritis, a group of medications known as disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, or DMARDs, may help to slow or stop the progress of the disease. They work by suppressing or interfering with the immune system. DMARDs include such drugs as penicillamine, methotrexate, oral or injectable gold, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine. DMARDs are not suitable for all patients with RA, however, as they sometimes have serious side effects. In addition, some of them are slow-acting and may take several months to work before the patient feels some relief.

LIFESTYLE CHANGES. A second alternative to knee surgery is lifestyle changes. Losing weight helps to reduce stress on the knee joint. Giving up specific sports or other activities that damage the knee, such as jogging, tennis, high-impact aerobics, or stair-climbing exercise machines, may control the pain enough to make surgery unnecessary. Wearing properly fitted shoes and avoiding high heels and other extreme styles can also help to control pain and minimize further damage to the knee.

BRACES AND ORTHOTICS. Some patients with unstable knees are helped by functional braces or knee supports that are designed to keep the kneecap from slipping out of place. Orthotics, which are inserts placed inside shoes, are often helpful to patients whose knee problems are related to their gait. Orthotics are designed either to correct the position of the foot in order to keep it from turning too far outward or inward, or to correct problems in the arch of the foot. Some orthotics are made of soft material that cushions the foot and are particularly helpful for patients with osteoarthritis or diabetes.

Complementary and alternative (CAM) approaches

Complementary and alternative therapies are not substitutes for arthroscopy or joint replacement surgery, but some have been shown to relieve physical pain before or after surgery, or to help patients cope more effectively with the emotional and psychological stress of a major operation. Acupuncture, chiropractic, hypnosis, and mindfulness meditation have been used successfully to relieve the pain of osteoarthritis as well as postoperative discomfort. According to Dr. Marc Darrow, author of The Knee Sourcebook , a plant extract called RA-1, which is used in Ayurvedic medicine to treat arthritis, relieved pain and leg swelling in patients participating in a randomized trial. Alternative approaches that have helped patients maintain a positive mental attitude include meditation, biofeedback, and various relaxation techniques.

Alternative surgical procedures

Arthroscopy is the most common surgical alternative to knee replacement. It should be understood, however, as a way to postpone TKR rather than avoid it completely. The arthroscopic procedure most often used to treat knee pain from osteoarthritis is debridement, in which the surgeon cuts or scrapes away damaged structures or tissues until healthy tissue is reached. Most patients who have had arthroscopic débridement have been able to postpone TKR for three to five years.

Cartilage transplantation is a procedure in which small bone plugs with cartilage are removed from a part of the patient's knee where the cartilage is still healthy and transplanted to the area in which cartilage has been damaged. Another form of cartilage transplantation involves two operations, one to remove cartilage cells from the patient's knee for culture in a laboratory, and a second operation to place the new cells within the damaged part of the knee. The cultured cells are covered with a thin layer of tissue to hold them in place. After surgery, the cartilage cells multiply to form new cartilage inside the knee. Unfortunately, as of 2003 neither form of cartilage transplantation is usually beneficial to patients with osteoarthritis; transplantation has been most successful in treating patients whose knee cartilage was damaged by sudden trauma rather than by gradual degeneration.

See also Arthroscopic surgery ; Knee revision surgery .

Resources

books

Darrow, Marc, MD, JD. The Knee Sourcebook. Chicago and New York: Contemporary Books, 2002.

Nohava, Ann. My Bilateral Knee Replacement: A Personal Story. San Jose, CA and New York: Writers Club Press, 2001.

Silber, Irwin. A Patient's Guide to Knee and Hip Replacement: Everything You Need to Know. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999.

periodicals

Alemparte, J., G. V. Johnson, R. L. Worland, et al. "Results of Simultaneous Bilateral Total Knee Replacement: A Study of 1208 Knees in 604 Patients." Journal of the Southern Orthopaedic Association 11 (Fall 2002): 153–156.

Blake, V. A., J. P. Allegrante, L. Robbins, et al. "Racial Differences in Social Network Experience and Perceptions of Benefit of Arthritis Treatments Among New York City Medicare Beneficiaries with Self-Reported Hip and Knee Pain." Arthritis and Rheumatism 47 (August 15, 2002): 366–371.

Chernajovsky, Y., P. G. Winyard, and P. S. Kabouridis. "Advances in Understanding the Genetic Basis of Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis: Implications for Therapy." American Journal of Pharmacogenomics 2 (2002): 223–234.

Crubezy, E., J. Goulet, J. Bruzek, et al. "Epidemiology of Osteoarthritis and Enthesopathies in a European Population Dating Back 7700 Years." Joint, Bone, Spine: Revue du Rhumatisme 69 (December 2002): 580–588.

Gunther, K. P. "Surgical Approaches to Osteoarthritis." Best Practice and Research: Clinical Rheumatology 15 (October 2001): 627–643.

Hasegawa, M., T. Ohashi, and A. Uchida. "Heterotopic Ossification Around Distal Femur After Total Knee Arthroplasty." Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery 122 (June 2002): 274–278.

Johnson, L. L. "Arthroscopic Abrasion Arthroplasty: A Review" Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 391 Supplement (October 2001): S306–S317.

Lombardi, A. V., T. H. Mallory, R. A. Fada, et al. "Simultaneous Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty: Who Decides?" Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 392 (November 2001): 319–329.

Mantilla, C. B., T. T. Horlocker, D. R. Schroeder, et al. "Frequency of Myocardial Infarction, Pulmonary Embolism, Deep Venous Thrombosis, and Death Following Primary Hip or Knee Arthroplasty." Anesthesiology 96 (May 2002): 1140–1146.

Parvisi, J., T. A. Sullivan, R. T. Trousdale, and D. G. Lewallen. "Thirty-Day Mortality After Total Knee Arthroplasty." Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, American Volume 83-A (August 2001): 1157–1161.

Peersman, G., R. Laskin, J. Davis, and M. Peterson. "Infection in Total Knee Replacement: A Retrospective Review of 6489 Total Knee Replacements." Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 392 (November 2002): 15–23. Shah, S. N., D. J. Schurman, and S. B. Goodman. "Screw Migration from Total Knee Prostheses Requiring Subsequent Surgery." Journal of Arthroplasty 17 (October 2002): 951–954.

Silva, M., R. Tharani, and T. P. Schmalzried. "Results of Direct Exchange or Debridement of the Infected Total Knee Arthroplasty." Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 404 (November 2002): 125–131.

Wai, E. K., H. J. Kreder, and J. I. Williams. "Arthroscopic Debridement of the Knee for Osteoarthritis in Patients Fifty Years of Age or Older: Utilization and Outcomes in the Province of Ontario." Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, American Volume 84-A (January 2002): 17–22.

organizations

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). 6300 North River Road, Rosemont, IL 60018. (847) 823-7186 or (800) 346-AAOS. http://www.aaos.org .

American Physical Therapy Association (APTA). 1111 North Fairfax Street, Alexandria, VA 22314. (703) 684-APTA or (800) 999-2782. http://www.apta.org .

Canadian Institute for Health Information/Institut canadien d'information sur la santé (CIHI). 377 Dalhousie Street, Suite 200, Ottawa, ON K1N 9N8. (613) 241-7860. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb .

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) Clearinghouse. P.O. Box 7923, Gaithersburg, MD 20898. (888) 644-6226. TTY: (866) 464-3615. Fax: (866) 464-3616. http://www.nccam.nih.gov. .

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) Information Clearinghouse. National Institutes of Health, 1 AMS Circle, Bethesda, MD 20892. (301) 495-4484. TTY: (301) 565-2966. http://www.niams.nih.gov .

Rush Arthritis and Orthopedics Institute. 1725 West Harrison Street, Suite 1055, Chicago, IL 60612. (312) 563-2420. http://www.rush.edu .

other

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) Patient Education Booklet #03057. Total Knee Replacement. Rosemont, IL: AAOS, 2001.

Canadian Institute for Health Information/Institut canadien d'information sur la santé (CIHI). Total Hip and Total Knee Replacements in Canada, 2000/01. Toronto, ON: Canadian Joint Replacement Registry, 2003.

Questions and Answers About Knee Problems. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 2001. NIH Publication No. 01-4912.

University of Iowa Department of Orthopaedics. Total Knee Replacement: A Patient Guide. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 1999.

Rebecca Frey, Ph.D.

WHO PERFORMS THE PROCEDURE AND WHERE IS IT PERFORMED?

Knee replacement surgery is performed by an orthopedic surgeon, who is an MD who has received advanced training in surgical treatment of disorders of the musculoskeletal system. As of 2002, qualification for this specialty in the United States requires a minimum of five years of training after medical school. Most orthopedic surgeons who perform joint replacements have had additional specialized training in these specific procedures.

Knee replacement surgery can be performed in a general hospital with a department of orthopedic surgery, but is also performed in specialized clinics or institutes for joint disorders.

QUESTIONS TO ASK THE DOCTOR

- How many knee replacements have you performed?

- Should I consider bilateral knee replacement?

- Will I benefit from arthroscopy or should I have knee replacement surgery now?

- What activities will I have to give up permanently if I have TKR?

- Does the hospital or clinic have preop classes to help me prepare for the operation? If not, are there knee exercises you would recommend before the surgery?